Historic Annapolis acquires, preserves, and displays objects that illuminate life in Annapolis, Maryland, and the Chesapeake region. Comprising about 3,000 objects, the Historic Annapolis collection ranges in scope from the seventeenth century to the present. For more highlights on collections items and other curatorial tidbits, visit the Collections section of the Historic Annapolis Blog.

Enrich the Historic Annapolis Collection

Donate or loan items for display in the William Paca House. Items from 1760-1780, the period when Paca owned the home, will help guests to the home visualize the many daily activities that took place there. Donations of objects that relate to the rich history of the City of Annapolis are also considered. Please contact Elizabeth Fox, Curator, for more information: 443.221.6962 or elizabeth.fox@annapolis.org.

Paca Family Salt Cellars

William Paca, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and his wife, Mary, either purchased or were given these two salt cellars from England in 1763. Significantly, this date also marks both the year of their marriage and the year that construction began on their home, the William Paca House and Garden, which was saved, restored, and is still maintained today by Historic Annapolis. This pair of oval salt cellars by London silversmiths, David and Robert Hennell, feature four curving feet attached to the body with “shells” that terminate in pad feet. A band of gadrooning decorates the rims of each and inscribed on the side of their bowls, the intertwined initials W, P, and M form a delicate monogram. It is not known whether the couple’s initials were engraved onto the cellars before or after they were shipped to Annapolis.

William Paca, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and his wife, Mary, either purchased or were given these two salt cellars from England in 1763. Significantly, this date also marks both the year of their marriage and the year that construction began on their home, the William Paca House and Garden, which was saved, restored, and is still maintained today by Historic Annapolis. This pair of oval salt cellars by London silversmiths, David and Robert Hennell, feature four curving feet attached to the body with “shells” that terminate in pad feet. A band of gadrooning decorates the rims of each and inscribed on the side of their bowls, the intertwined initials W, P, and M form a delicate monogram. It is not known whether the couple’s initials were engraved onto the cellars before or after they were shipped to Annapolis.

The cellars were purchased at auction by Historic Annapolis in 1972 from the collection of John Adam Horn of Towson, Maryland; the salt cellars were sold with other silver items owned by William and Mary Paca. John W. Paca of Baltimore, a descendant of the signer’s family, helped fund the purchase.

The “Tallio” Cufflink

This brass cufflink (or “sleeve button” as they were called in the eighteenth century) was recovered from the archaeological excavations of the William Paca garden in the 1960s. Found amongst pottery fragments in the same archaeological layer, this sleeve button can be dated to the time when William Paca lived at his Prince George Street home; this sleeve button was possibly worn by the signer himself. Although the design has lost its clarity over the centuries, it is still possible to distinguish the image of a running fox and the word “tallio.” This gives the sleeve button a novelty appearance and shows that during his leisure time, William Paca might well have been a keen foxhunter. William Paca was not the only man in the colonies to own such a cufflink. The same design was popular in eighteenth-century America and identical sleeve buttons have also been found at Williamsburg and Ferry Farm, George Washington’s childhood home.

This brass cufflink (or “sleeve button” as they were called in the eighteenth century) was recovered from the archaeological excavations of the William Paca garden in the 1960s. Found amongst pottery fragments in the same archaeological layer, this sleeve button can be dated to the time when William Paca lived at his Prince George Street home; this sleeve button was possibly worn by the signer himself. Although the design has lost its clarity over the centuries, it is still possible to distinguish the image of a running fox and the word “tallio.” This gives the sleeve button a novelty appearance and shows that during his leisure time, William Paca might well have been a keen foxhunter. William Paca was not the only man in the colonies to own such a cufflink. The same design was popular in eighteenth-century America and identical sleeve buttons have also been found at Williamsburg and Ferry Farm, George Washington’s childhood home.

The motif and lettering gives us a clear indication that the owner enjoyed foxhunting. “Tallio,” a quaint spelling of Tally-Ho, demonstrates that the vernacular of the British hunting gentry was easily transferred to America where the sport continued to be practiced.

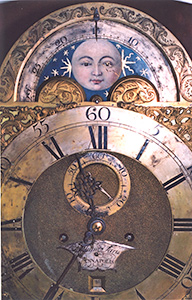

Faris-Shaw-Chisholm Tall-Case Clock

This handsome mahogany tall case clock is one of the nation’s most treasured examples of craftsmanship in the field of clockwork. Among other unique features, it is the only William Faris and John Shaw collaboration that has ever come to light. John Shaw, born in Glasgow in 1745 and arrived in Annapolis in 1763, is considered one of the preeminent cabinetmakers of Annapolis during the Federal period. Shaw and his students helped bring the Neo-Classical style to Annapolis homes and public buildings. These furnishings in turn influenced the architecture built around them, both public and private, keeping the city at the forefront of style in colonial America.

This handsome mahogany tall case clock is one of the nation’s most treasured examples of craftsmanship in the field of clockwork. Among other unique features, it is the only William Faris and John Shaw collaboration that has ever come to light. John Shaw, born in Glasgow in 1745 and arrived in Annapolis in 1763, is considered one of the preeminent cabinetmakers of Annapolis during the Federal period. Shaw and his students helped bring the Neo-Classical style to Annapolis homes and public buildings. These furnishings in turn influenced the architecture built around them, both public and private, keeping the city at the forefront of style in colonial America.

A surviving label allows us to date the clock fairly accurately. John Shaw and Archibald Chisolm, also from Scotland, worked in partnership for only a short time between 1772 and 1776. During this period, clockmakers engraved their names on the dial as a mode of advertising. Moon dials, as seen on this clock, involved movements that were considerably more sophisticated and displayed the phases of the moon in tandem with the time on the clock itself. This piece is also unique as it is the only known Faris moon dial still with its original case. The painted moon face is exquisitely rendered and the unusual quality of its extreme detail suggests the work of a fine portrait painter or highly trained miniaturist.

The clock was purchased at auction by Historic Annapolis at the recommendation of the descendants of its last owner, Eleanor Adams, and had belonged to the family since its construction. After its purchase in 2004 from Headley’s Auctions, the clock was painstakingly restored between 2006 and 2012 with funds from the Winifred M. Gordon Foundation. The clock still keeps time in the dining room at the William Paca House today.

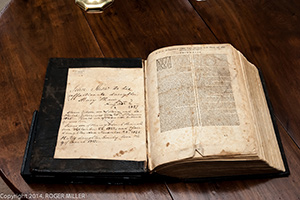

John Shaw Bible

A remarkable survival after its discovery in the trash, this Bible belonging to the celebrated Annapolitan cabinetmaker, John Shaw, was given to Historic Annapolis in 1956 and became the first item ever accessioned into its collection. This Bible was printed in London in 1766. Throughout the book, on the blank pages between sections (such as the psalms or prayers) the Shaw family recorded their marriages, the births of their children, and the deaths of their spouses, among other milestones. Shaw even notes his bequeathal of this Bible to his daughter, Mary, two years before his death within the volume itself. These events were carefully recorded within the Bible to preserve this information for posterity, adding an extreme sense of irony to its later rediscovery in the trash.

A remarkable survival after its discovery in the trash, this Bible belonging to the celebrated Annapolitan cabinetmaker, John Shaw, was given to Historic Annapolis in 1956 and became the first item ever accessioned into its collection. This Bible was printed in London in 1766. Throughout the book, on the blank pages between sections (such as the psalms or prayers) the Shaw family recorded their marriages, the births of their children, and the deaths of their spouses, among other milestones. Shaw even notes his bequeathal of this Bible to his daughter, Mary, two years before his death within the volume itself. These events were carefully recorded within the Bible to preserve this information for posterity, adding an extreme sense of irony to its later rediscovery in the trash.

Peale Portrait of John Philemon Paca

This delicately conceived portrait depicts William Paca’s heir, John Philemon Paca (1771-1840), his only surviving child from his first marriage to Mary Chew Paca. The work has been attributed to the celebrated portraitist Charles Willson Peale by several scholars. John Philemon’s portrait displays marked stylistic similarities to other Charles Willson Peale paintings, particularly several portraits conceived within the 1780s, a period that corresponds to the age of the adolescent sitter. The particular red tone of the young man’s lips and cheeks, the smooth, oval-shaped head with full chin, strongly defined arched eyebrows, and fullness of the mouth are characteristic of many Charles Willson Peale portraits.

This delicately conceived portrait depicts William Paca’s heir, John Philemon Paca (1771-1840), his only surviving child from his first marriage to Mary Chew Paca. The work has been attributed to the celebrated portraitist Charles Willson Peale by several scholars. John Philemon’s portrait displays marked stylistic similarities to other Charles Willson Peale paintings, particularly several portraits conceived within the 1780s, a period that corresponds to the age of the adolescent sitter. The particular red tone of the young man’s lips and cheeks, the smooth, oval-shaped head with full chin, strongly defined arched eyebrows, and fullness of the mouth are characteristic of many Charles Willson Peale portraits.

Peale knew the Paca family well; in fact, he was friends with both William Paca and John, his father. In 1788, Peale came to repair his 1772 portrait of William Paca, which shows him full-length, with a magnificent background of the pleasure garden at his Prince George Street home. It is entirely possible that during this trip to Maryland to visit the family he also painted this portrait of John Philemon, Paca’s son.

Maryland Easy Chair

This Maryland piece dates to about 1780 and is not only one of the most significant items in Historic Annapolis’s collection, but in the American decorative arts field as a whole. The extraordinary survival of its original upholstery (the beige linen) warranted an in-depth forensic study of the piece by the upholstery conservators at Historic New England.

This Maryland piece dates to about 1780 and is not only one of the most significant items in Historic Annapolis’s collection, but in the American decorative arts field as a whole. The extraordinary survival of its original upholstery (the beige linen) warranted an in-depth forensic study of the piece by the upholstery conservators at Historic New England.

Over the course of more than two centuries, the vast majority of easy chairs from this period have had their under linens stripped off (often along with the materials they were stuffed with) and replaced with a fitted “show” fabric. The study of this particular chair, with many of its original materials intact, gave scholars new insight into early construction techniques. Close analysis of this mahogany chair found the under linen, webbing, dried grass, horsehair, and rose-head iron tacks to be original to its first construction. All these materials (and some strange eighteenth-century detritus that was found inside the chair during conservation!) are on display alongside the chair.

With the slip covers removed, one can fully admire the elegant arabesque rococo curves of the chair’s silhouette. The semi-opaque polyester covering that now encases the chair allows its construction techniques to be admired whilst preventing further damage.

William Paca Bed

This fine Maryland-made bed dates to the 1780s and is a new and noteworthy addition to the collection. The bed has a long oral tradition associated with William Paca, which can be traced to the late nineteenth century. Further research into the donor’s family history has substantiated these claims regarding its provenance.

This fine Maryland-made bed dates to the 1780s and is a new and noteworthy addition to the collection. The bed has a long oral tradition associated with William Paca, which can be traced to the late nineteenth century. Further research into the donor’s family history has substantiated these claims regarding its provenance.

Although the dearth of William Paca-owned objects still in existence makes this piece significant, the bed might also infer more about the owner. With evidence from inventories, some have suggested that the William Paca sold his Prince George Street home complete with furnishings. This Federal-style bed, with its restrained doric posts and clean lines could reinforce this theory. A man of Paca’s means could well have sold his house furnished in the older, rococo style to order to purchase fashionable Federal pieces for his newly built mansion, Wye Hall.

Carvel Hall Taproom Sign

The rich history of the William Paca House transcends the colonial era to which the house is currently interpreted. In 1902 the building was expanded into Carvel Hall, a vast, two-hundred-room hotel, which stood for half a century. Not only does this wooden sign represent a moment in the building’s history, but it also characterizes a movement within Annapolis in the 1930s and 1940s to preserve and protect the city’s colonial past.

The rich history of the William Paca House transcends the colonial era to which the house is currently interpreted. In 1902 the building was expanded into Carvel Hall, a vast, two-hundred-room hotel, which stood for half a century. Not only does this wooden sign represent a moment in the building’s history, but it also characterizes a movement within Annapolis in the 1930s and 1940s to preserve and protect the city’s colonial past.

In 1943, the owners of Carvel Hall commissioned Jack Manley Rosé to recapture colonial Annapolis at “the peak of its perfection” in a set of monumental murals in its restaurant, The Old Annapolis Taproom. In the accompanying brochure, the proprietors also described the works as a visual record; this statement suggests a fear for the future of the city and its “vanishing glories.”

Rosé lent his background illustrating a book on Williamsburg and various pediodicals to the work, consulting with the hotel manager at length to ensure historical accuracy. Scenes included State Circle, St. John’s College, the Hammond-Harwood House, the William Paca House, Reynolds Tavern, and a selection of other buildings and vistas. In the 1960s, the murals were removed as part of the Paca House’s restoration. Though the murals remain in storage without adequate space for reinstatement, Historic Annapolis purchased Rosé’s sign for the Taproom, which offers a window into this fascinating history.

For more information on donating an object to the collection or making a cash donation to the Collection Fund, please contact:

Elizabeth Fox

Curator

443.221.6962

elizabeth.fox@annapolis.org