This year Annapolis celebrates the 200th anniversary of the Marquis de Lafayette’s Farewell Tour of America in 1824 – 1825. Invited as a “Guest of the Nation” by President James Monroe, Lafayette was welcomed with much enthusiasm and celebration by Americans in all 24 states in the Union. As the last surviving general of the American Revolution, Lafayette inspired a patriotic retrospective for Americans in the post-Revolutionary War period.

The city of Annapolis has long held affection for the Marquis de Lafayette. From his early days as a young, idealistic solider to later in life as a seasoned statesman, Lafayette had a personal connection to the capital city of Maryland that is still honored today.

In December of 1824, after a 40-year absence, Lafayette made one last trip to Annapolis accompanied by his son, George Washington Lafayette. As part of his 13-month farewell “Grand Tour” of the United States, he spent four days in Annapolis in December 1824, allowing a new generation of townspeople a glimpse of one of the nation’s most revered heroes. Festivities included a military procession and exhibition, an official reception in the State House, and a dinner and ball at St. John’s College.

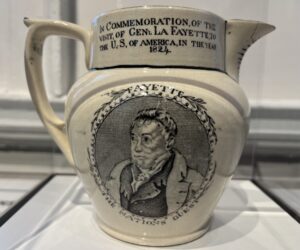

In celebration of Lafayette’s return visit, his likeness appeared on everything from banners to gloves, plates, and pitchers such as this. These souvenirs provided tangible connections with an icon of the past.

SPECIAL APPEARANCE: MEET JAMES LAFAYETTE ON SATURDAY, DECEMBER 14

Portrayed by historical interpreter Stephen Seals, visitors can learn the story of James Lafayette, a spy who gained his freedom through his brave and heroic actions during the Revolutionary War. The Marquis de Lafayette intervened personally in 1784, detailing James’ service during the Revolution. To honor their friendship, James Lafayette adopted Lafayette as his surname. Meet James at the Museum of Historic Annapolis at 99 Main Street on Saturday, December 14 between 11 am and 3 pm.

Events

Tuesday, December 10

- Virtual Lecture with Dr. Amy Rosenkrans – Maryland Women and Lafayette, 7 pm, Zoom Webinar (advance registration required)

Friday, December 13 – Sunday, December 15

- Open House Weekend at additional Museums throughout Annapolis:

- Hammond Harwood House, 19 Maryland Avenue (admission fee)

- United States Naval Academy Museum, (Preble Hall), corner of Maryland Avenue and Decatur Road. Valid government ID required for access to Naval Academy grounds (Saturday – Sunday, no admission fee)

- Watermark, 188 Main Street, Annapolis 12:00pm – 4:00pm (Saturday only)

- Chase Lloyd House Dependency, corner of Maryland Avenue & King George Street (Sunday only)

Saturday, December 14

- Meet James Lafayette! at the Museum of Annapolis, 11 am – 3 pm

- Pop-up Exhibit at the Museum of Historic Annapolis: The Marquis de Lafayette, 11 am – 3 pm

- Storytime at the Museum: A Spy Called James (The True Story of James Lafayette) at the Museum of Historic Annapolis, 11 am and 1 pm

- Children’s Games from Long Ago presented by Chesapeake Children’s Museum at Visit Annapolis, 26 West Street, 10 am – 12 pm

- Colonial Walking Tour with Lafayette Focus (USNA add-on option) with Watermark, 188 Main Street, 10 am

- Book Talk and Signing by Bruce Mowday, author of “The Battle of Brandywine”, St. John’s College Bookstore at Edensword Hall, 60 College Avenue, 11 am – 12:30 pm

- Open House and Author’s Storytime with Selene Castrovilla at Watermark’s Tour Office, 188 Main Street, 12 pm – 4 pm (book talks at 1 pm and 3 pm)

- Maryland State House Tour with Lafayette Focus with Watermark, 188 Main Street, 1:30 pm

- Music for Marquis de Lafayette at Chesapeake Children’s Museum, 25 Silopanna Road, 2 pm and 3 pm

- Lafayette in Annapolis-200 Years Ago – Special Tour at the Hammond-Harwood House, 19 Maryland Avenue, 3 pm

- SOLD OUT – Marquis de Lafayette Holiday Tea

- A Night of Splendour and Elegance: Lafayette Bicentennial Grand Ball at McDowell Hall, 7:30 pm – 10:30 pm

Sunday, December 15

- Brunch with General Lafayette and Mary Nevett Steele, with a Lecture by Glenn Campbell at O’Brien’s Restaurant, 113 Main Street, 9:30 am

- Colonial Walking Tour with Lafayette Focus (USNA add-on option) with Watermark, 188 Main Street, 10 am

- Pop-up Exhibit at the Museum of Historic Annapolis: The Marquis de Lafayette, 11 am – 3 pm

- ASO Youth Orchestra Presents Music of the Time of Marquis de Lafayette at Chase-Lloyd House Dependency, corner of King George Street and Maryland Avenue, 12:30 pm – 1:30 pm (free and open to public)

- The Blue Jays Present “Lafayette” and Other Period Music at Chase-Lloyd House Dependency, corner of King George Street and Maryland Avenue, 1:30 pm – 3 pm (free and open to public)

- Maryland State House Tour with Lafayette Focus with Watermark, 188 Main Street, 1:30 pm

- Bicentennial Concert at State House for General Lafayette with David and Ginger Hildebrand, Maryland State House, 100 State Circle, 2:30 pm (free and open to public, state ID required to enter building)

Contact Us

For more information about the Lafayette Bicentennial Tour, please click here, or contact us at info@annapolis.org.

In 1777, the 19-year-old French officer Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, passed through Annapolis as he traveled to Philadelphia to volunteer for America’s revolutionary cause. Commissioned as a Major General by Congress, Lafayette soon joined George Washington’s staff and began a life-long friendship with him.

Six months before the Yorktown campaign, in the spring of 1781, Continental Army troops under Lafayette’s command camped in Eastport on the banks of Spa Creek while he contemplated a campaign against the traitorous Benedict Arnold and the British in Virginia.

Annapolis women were impressed with the dashing Frenchman. Margaret Ogle wrote about Lafayette and his entourage: “The town is so dull it would be intolerable were it not for the officers. . . . I like the French better every hour. The divine Marquis de la Fayette is in town, and is quite the thing. We abound in French officers, and some of them are very clever . . . . I have seen one tolerable American among them, . . . one of the marquis’s family [staff]; perhaps that has polished him.”

Lafayette continued to Virginia by himself, where he quickly learned enough to decide that he shouldn’t go ahead with the mission, then he returned to his men in Annapolis. Two British ships attempted to blockade him and his troops, but they managed to get away safely and sailed back north up the Chesapeake Bay. They then marched south again by an inland route.

In September 1781, American and French troops passed through Annapolis on the way to Yorktown, but Lafayette was not with them, as he had already spent the summer months maneuvering against the British in Virginia. Annapolitans warmly welcome the passing French troops.

“No place in the Colonies was perhaps better adapted to give the French officers a sympathetic reception. Annapolis was in America what Paris was in France, the center of fashion, refinement and luxury. As the Abbé Robin, a chaplain in the French army, said after visiting it at this time:”

“That very inconsiderable town . . . out of the few buildings it contains, has at least three-fourths such as may be styled elegant and grand. Female luxury here exceeds what is known in the provinces of France; a French hairdresser is a man of importance among them, and it is said a certain dame here hires one of that craft at a thousand crowns a year salary. The State House is a very beautiful building, I think the most so of any I have seen in America. The peristyle is set off with pillars, and the edifice is topped with a dome.” (Annapolis: Its Colonial and Naval Story • Chapter 11, n.d.)

The city of Annapolis’s respect for all the French soldiers and sailors who fought in the American Revolution is symbolized by a granite monument that honors those who died and were buried here. A monument was erected in 1911 at St. John’s College, marking the burial site of a number of unknown French casualties.

Lafayette went back to France after the victory at Yorktown but soon returned to the newly independent United States. In late 1784, he accompanied Washington to Annapolis, and while at the State House, Governor William Paca and the Maryland legislature praised and entertained the pair. Within days of their departure, Maryland’s government passed an act making “the Marquis de Lafayette, and his heirs male forever … natural born citizens of this State.”

In response to this honor, “With the ardor of a most zealous heart,” Lafayette wished Maryland “will to the fullest extent improve her natural advantages, and in the Federal Union so necessary to all, attain the highest degree of particular happiness and prosperity.” (Lafayette Becomes “Quite the Thing” in Annapolis, n.d.)

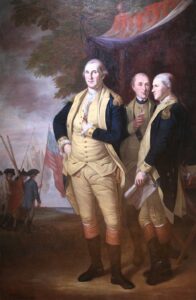

Lafayette and Washington would also have the pleasure of seeing their newly painted portrait, also featuring Tench Tilghman, by Charles Willson Peale hanging in the House of Delegates Chamber. (Lafayette Becomes “Quite the Thing” in Annapolis, n.d. -comment Elaine Rice Bachmann June 26, 2014)

Beyond his military success in the pivotal battle of Yorktown, the French general was an ardent advocate for human rights. He believed in racial equality and campaigned for the abolition of slavery. “After the American Revolution, Lafayette returned to France where his popularity soared as he navigated the tenuous line between the angry subjects and the monarchy.” (Marquis De Lafayette, n.d.)

He helped write the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, a document which would advance the French Revolution. In his pursuit of social justice, Lafayette defended religious rights for “French Protestants and Jews, spoke out against capital punishment and solitary confinement, and supported women and their ideas and causes.” (Lafayette College, 2022)

Lafayette fled from France when the revolution turned violent. He suffered imprisonment at Olmütz from 1792-1797 by the Austrians who considered him a dangerous radical. Lafayette’s fortune was confiscated by the French government and many of his wife’s family died by the guillotine. When Lafayette was finally able to return to France, he settled at La Grange, an estate near Paris.

During the era of the Restoration of the monarchy, Lafayette returned to public life but most of his political activity took the form of direct communications including his thoughts on slavery in the United States. In a letter to Thomas Jefferson in 1822, Lafayette wrote: “While I feel an inexpressible delight in the progress of Every thing that is Noble minded, Honourable, and Useful throughout the United States, I find, in the Negros Slavery, a great draw-Back Upon My Enjoyments. … this Wide Blot On American Philantropy and Civilisation is Ever thrown in my face When I indulge my Patriotism in Encomiums, otherwise Undisputable. … I Would Like, Before I die, to be assured that progressive and Earnest Measures Have Been adopted to Attain, in due time, So desirable So necessary an object.”

Annapolis: Its Colonial and Naval Story • Chapter 11. (n.d.)

Kloss, M. (n.d.). Washington, Lafayette & Tilghman at Yorktown by Charles Willson Peale

George Washington’s Mount Vernon. (n.d.). Marquis de Lafayette

Lafayette and Slavery – Lafayette Society. (2018, June 15). Lafayette Society

Lafayette becomes “Quite the Thing” in Annapolis. (n.d.)

Lafayette College. (2022, February 22). The Marquis de Lafayette – About